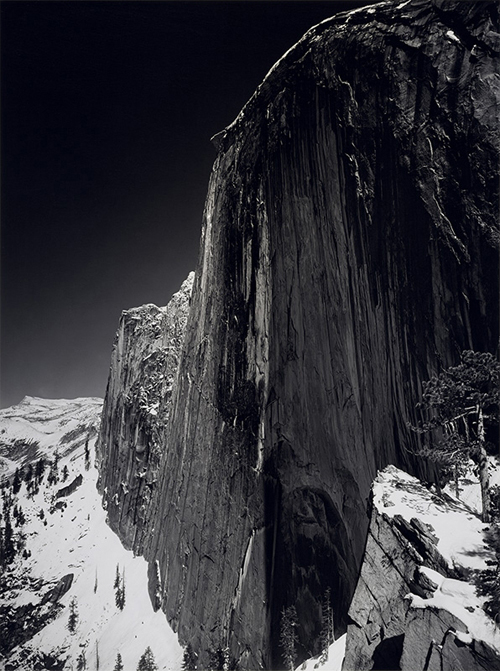

Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Ansel Adams.

Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Ansel Adams.

“I had been able to realize a desired image: not the way the subject appeared in reality but how it felt to me and how it must appear in the finished print”

When I started this series I knew I was going to have to write about Ansel Adams (1902-1984). People would roll their eyes and say, yes, we know Ansel. But, believing there remains a fundamental difference between being familiar with Adams’ work, and studying it, I still think there’s value in considering him a master. He is one of the giants on whose shoulders people like Edward Burtynsky, or Galen Rowell, stand (and stood). Sure, he’s been overplayed a little, like the Beatles’ Yesterday, but try to see it for what it was, and to see him for who he was, and learn something from both of those.

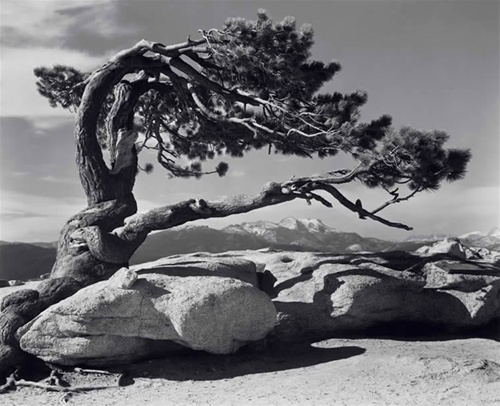

Jeffrey Pine, Ansel Adams

Jeffrey Pine, Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams was a defining figure in the romantic tradition of 19th century American landscape photography. He studied piano and planned to become a concert pianist before switching paths and becoming a photographer. He worked mainly with large format cameras in the American west, and was particularly known for his high contrast photographs of Yosemite, photographs that I carefully cut from calendars and put on my walls as a teenager, beside National Geographic covers from people like Steve McCurry, and photographs from the Patagonia catalogue. That sums up my early influence tidily. And like me, Adams seemed driven by more than a desire to make an accurate recording or pretty picture, but to move people to preserve a place he loved by creating in them a sense of mystery and the sublime. Like Burtynsky who I featured last week, Adams had an agenda – his photography supporting his environmentalist and conservationist hopes. Adams believed photography could create a strong emotional response in viewers, and his resulting efforts played a huge role in American conservation efforts of his time.

“More than any other influential American of his epoch, Adams believed in both the possibility and the probability of humankind living in harmony and balance with its environment.” – William Turnage

There’s much to learn from Adams. He still did commercial work to pay bills, but kept that work separate from his personal work, a model more photographers might consider, giving them both more creative and financial freedom. He played a role in furthering the craft, developing the Zone System with Fred Archer, and introducing early ideas about visualization. And his work was unique, speaking with a strength of individual voice that’s hard to ignore. His careful compositions, strong tonal contrast, and attention to the whole process – from vision to negative to print – might shame many of us who have become sloppy in our craft. Almost any of us now working in a landscape tradition have been influenced by Adams, even indirectly, and owe to him, in part, a debt for the place photography is slowly taking in the art world.

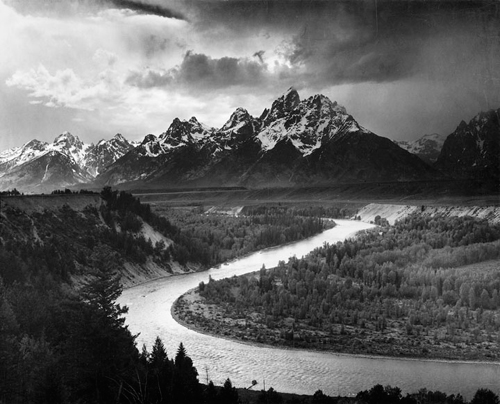

The Tetons and the Snake River, Ansel Adams.

You can learn more about Ansel Adams on the official website.

You can study his work in greater detail in these three, among many, books:

Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs

Ansel Adams: The Camera (The Ansel Adams Photography Series 1)

Comments

Like you David- I too love those Patagonia catalog mountain photos – I thought I was the only one clipping out those pages from Chamonix and Torres del Paine!

Hey David,

The power of Adam’s art is in the printed image. Much of what we do today in photography never sees itself in a beautifully printed image. Adams was able to visualize the final image and achieve the desired effect through his mastery of all aspects of making a work of art that was the final print.

Enjoying the Master’s series!

Best,

Craig

Great post, David. For me, the thing about Ansel Adams was his understanding of light, and how to create the effect he wanted through exposure. The zone sŷstem!

Great choice of images, there is always a stunning simplicity in his work. I think there are so many landscapes and settings around us that we miss that he would have been capturing. As Paul mentioned, this was all captured on a large format camera!

Superb article David. I don’t know America particularly well and the first image, is the terrain reasonably accessible? I ask for either way, what dedication to haul large format around in pursuit of an image. And here in 2014 many complain about carrying a slr. Humbled.

Psul,

No, the terrain is not reasonably accessible. The point where Ansel stood to make that photograph is a little over a 1000m gain above the starting point for the hike, which also involves some moderately challenging route finding as well as some class 3 scrambling. Many people forget that Adams was an accomplished hiker and even a reasonable mountaineer in his early days.