Have you ever looked at one of your photographs and thought, is it any good? I often wonder if this is the one big question that goes through the minds of most photographers, after the one about whether we should get another camera bag, which is ridiculous, because you can never have too many camera bags.

Is it any good?

Holy moly, how do we even begin to answer that? I’ll tell you how: we go online and we ask thousands of other people, equally unable to give a response that is more reasoned than I like it. And that’s if we’re lucky. No wonder some of us feel like we’re spinning our wheels. And when we’re really new at this craft, “good” might mean making a photograph that’s nothing more than in focus and reasonably well exposed (and there’s nothing wrong with that), but surely our standards change as we grow, and what we mean by the question should probably change too.

I think there’s a better question. What if we stopped wondering if it’s good? What if instead we asked, did I succeed? What did I want to say with this photograph and did I say it? Did I get there? Those are better questions; they can be answered, and even if we don’t have a strong yes or no in reply, you can at least begin to zero in on it and listen to your gut in a more specific way.

Asking “is it good” is not just a moving target, but a target moving like a 4-year-old child on a red-line sugar high.

It’s not just one question but a million questions in waiting. Do you mean technically? Do you mean in context with your other photographs and your own development as a photographer? Do you mean is it good like the work of Ernst Haas? What do you mean?

Asking yourself whether your photograph succeeded or not is also a big question that leads to many more, but at least those resulting questions can help you get somewhere. They lead us all further down the rabbit hole of discovering or clarifying our own vision or intent rather than outward into the un-answering void.

I think vision is a complicated thing, and by that one word, we mean many things. But let’s leave it at just this for now: what do you want to accomplish with this photograph?

It could be you have no idea. For many of us, we raise the camera to the eye for the sheer joy of seeing what the world looks like through the lens with a frame around it. For many of us, the camera helps us see, and it’s not until after we’re looked through the lens and made a few sketch images that we begin to understand what the heart of the photograph is. And only then do we begin to get a sense of what it might mean for the photograph to succeed.

Exploration is often the necessary first step, and it’s OK to go in blind and stumble around for a while to get your bearings. With all his talk about pre-visualizing, I suspect Ansel Adams had a superpower I don’t have.

If you have no idea what you want to accomplish, then you’re not at the point where you should be asking yourself if you accomplished it. You should still be exploring and finding that one thing that your photograph is about. Is it the mood? Is it the story? Is it the play of light on leaves or the way your son, backlit on the living room floor, giggles as he plays with his toys (which is a little weird because he’s 35 and should be out of the house by now)?

What are you trying to say, to point at, to express?

Trying is the key word. So we should all cut ourselves a little slack knowing that what works for me won’t work for everyone. Does my effort to capture that one thing scratch my own itch? Of course, I hope it does something for other people: makes them feel something, remember something, question something. But it first has to work for me. It has to be my own voice saying something that is important to me in that photograph. Only then can I have some idea if the photograph works, or succeeds. Or at least I’ll have a sense of what I mean when I ask the question.

And if the answer is no, it gives me a starting place to ask more questions. What changes would help me better zero in on what should be, for me, the heart of the photograph? Do I need to exclude more? (This is often the answer.) Do I need to change my point of view or my lens? Do I need to wait for a stronger moment? Wait for more suitable light? Get less literal and use slower shutter speeds or multiple exposures?

I’m going to put my cards on the table here and give you a no B.S. opinion, and you can take it or leave it:

I don’t think most photographs fail because they are technically inadequate. I think they fail because they have nothing to say, and that’s not the fault of the photograph. Or the camera.

It’s because we didn’t stop to ask what we wanted. Not just a photograph of a kid in a village in Tibet, but what do you want to say about that child? Not just a beautiful landscape, but what, specifically, do you want to show me? What do you want me to feel? You can’t show it all, or say it all. Our medium is limited, so we need to be choosy.

When my own images don’t work for me, it’s almost always first because I’ve not been specific enough about what I wanted to show. They’re sharp but really have nothing to say. And that makes it really hard to evaluate whether I succeeded or not. And that’s when I find myself defaulting to the less helpful question of, is it any good? Because that latter question is so nebulous that it’s just easier to fall back on the technical merits and assure my fragile ego that yes, in fact, it is good. It’s a really sharp, really big, perfectly crafted photograph about nothing in particular. Yawn.

You see, no one cares about “good” when it comes to photographs. We want more.

Better to ask if the image is (and here’s where it’ll help to know what you wanted the image to do in the first place) haunting or nostalgic, or…

- Does it make you feel a certain way?

- Does it cause you to look at something differently?

- Does it make you wonder?

- Does it make you wish you were there?

- Does it make you angry (and not just because you missed the focus or blew your highlights)?

These are much better questions, and they all depend on what you hoped to accomplish.

“But there’s no way I can be asking myself all these questions and still make 100 decent photographs this morning—or this week!”

Exactly. Slow down, friends. Take your time.

There’s no pressure to perform. Going back to Ansel Adams, he said a good year for him was making 12 photographs. I wonder if one of the reasons we don’t take a more mindful approach to our photography is because it would force us to go slower if we did. Consider this your permission to slow down. There’s no pressure. This isn’t a race, though you wouldn’t know it from looking at Instagram. Isn’t it better to make 12 photographs that we truly love, that truly do succeed, and do whatever it is we really want from our work, than to make 100 times that number, always wondering if they’re good? When it comes to learning and keeping your work moving forward, asking yourself what you want to accomplish and, later, whether or not you got there, is a much stronger starting place.

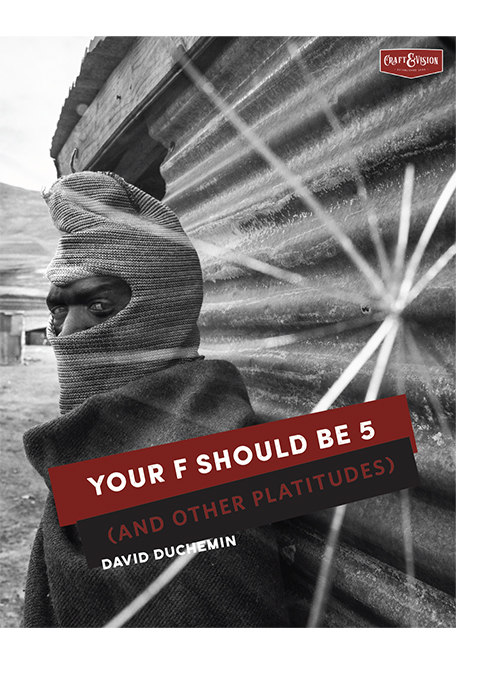

Want more articles like this? Our photographs are a result of our creativity and the choices we make, so they’re only as good as the way that we think. I’m happy to keep sending you new thoughts and ideas here in the Contact Sheet, but if you’d like a collection of my best articles, available to you anywhere, any time, you can get 50 of them in my newest digital book, Your F Should Be 5.

Want more articles like this? Our photographs are a result of our creativity and the choices we make, so they’re only as good as the way that we think. I’m happy to keep sending you new thoughts and ideas here in the Contact Sheet, but if you’d like a collection of my best articles, available to you anywhere, any time, you can get 50 of them in my newest digital book, Your F Should Be 5.

A few years ago I was photographing the Day of the Dead in Oaxaca, Mexico, and there was a workshop group eating at a little restaurant we’d ducked into for dinner. At the end they all got up and headed for the door and suddenly out of nowhere this one woman much-too-loudly said, “And remember, your F should be 5!”

My friends and I all looked at each other. What? My F should be 5? Does my F even have a 5?

Photographers love prescriptions. We love guidelines and rules and platitudes. But when those little mental shortcuts prevent us from thinking, our photographs start to show it. I’ve tried hard to be a voice that encourages a little more creativity in our thinking toward how and why we make photographs.

My latest eBook, Your F Should Be 5 (And Other Platitudes) is a 200-page compilation of some of my best recent writing, giving you easy, anytime-and-anywhere offline access to 50 thought-provoking articles to stir the paint, keep you focused, and remind you to think for yourself about the more important aspects of photographic craft and creativity. You can get Your F Should Be 5 at Craft & Vision for $18.

Comments

Lovely Article. Thank-you for sharing. Agree of the pressure to get better images and that’s needed to be removed. I feel its a life long journey, and should enjoy it

David, I found one of your books “The soul of the camera” in a local bookstore in Würzburg, Germany. The book is translated in german and I was starting to read it in the bookstore.

After a couple of sentences I was so excited and gave the book to my wife. We have discussed some of your thoughts and were one opinion with you. Your blog is awesome and I am looking forward to your next article. Thank you very much. All the best…

I’ve been traveling for 8 months non stop now and whenever I return to my room in the evening with 40 or 50 shots it has been a very busy day! I guess my mind is still stuck on working with film 😉 But I really like the slow way of working and it works for me…

By the way, isn’t Varanasi every photographer’s favorite place in India? 🙂

I posted a series of the ghats of Varanasi a while ago. Hope you like’em…

https://www.theworldaheadofus.com/blog/photo-essay-the-ghats-of-varanasi

Can’t wait to go back…

Cheers

Joris

Wow Amazing Place, I think this is Varanasi, India. Is it Right?

That’s right, Rahul! One of my favourite places!

Several years ago while attending college in a journalism program, I had a few portfolio reviews. My portfolio was made of technically competent photos but said “nothing”, and the reviewers (all professional photojournalists, including a putlitzer prize winner) could see it. The portfolio was a mish-mash of subjects and content, and they essentially told me to start over. It was suggested I should figure out what to say and make a portfolio of that. My problem at the time, and for years after, is that I was so emotionally guarded that I didn’t know *how* to express myself so deeply in life let alone photography. Telling me that my photographs should “say” something was akin to asking me a Zen Koan.

Fast forward to today through a few major life changes and I’ve grown dramatically. Reading this post and your suggestions bring me back to the past and allow me to reflect on how far I’ve come, and how your suggestions make complete sense. I now have answers to those questions you ask and that I must ask of my photography.

Thank you for being a vibrant and positive member of our visual artist community Dave!

David, I found one of your books “The soul of the camera” in a local bookstore in Würzburg, Germany. The book is translated in german and I was starting to read it in the bookstore.

After a couple of sentences I was so excited and gave the book to my wife. We have discussed some of your thoughts and were one opinion with you. Your blog is awesome and I am looking forward to your next article. Thank you very much. All the best.

Wonderful! Welcome here, Markus!

If you would like my blog articles sent directly to you, you can put your name on the list here, and get a free eBook at the same time:

https://craftandvision.lpages.co/20-ways-free-ebook-offer

Pingback: Flying with Purpose – Photography, Apps & Technology

Pingback: Monday Missive — July 16, 2018 | RichEskinPhoto.com: Nature, Fine Art and Conservation Photography

Another awesome article. Great advice and insight for photographers. Really appreciate it.

Lovely Article. Thank-you for sharing. Agree of the pressure to get better images and that’s needed to be removed. I feel its a life long journey, and should enjoy it (unless its profession). And if we can get 12 photos in a year which we can hang on wall/exhibit, then we have done enough part. Any ways thanks for it. Got his blog post link from a google+ community.

David, all of the pictures I call good are good! Period. And whoever cares may care. I am by no means, done yet.